“Hot tamales and they’re red hot, yes she got ‘em for sale.” Robert Johnson

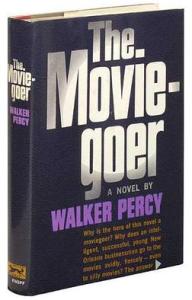

The sad and untimely death of writer Julia Reed a few weeks ago prompted me to embark on an all-day frenzy of making Mississippi Delta-style hot tamales. I believe she would have approved, given the Delta native’s celebration of both the hot tamale and grand gestures. I revelled in her columns and cable TV commentary; she was a mainstay of my Southern consciousness. Julia’s good humor and biting insights channeled the best of the eccentricity and joie de vivre I associate with my own relatives from the Mississippi Delta. Making hot tamales from scratch allowed me to both get busy in the kitchen and commune with both Julia and some aspects of my own personal history.

Much has been written and said about the Delta Hot Tamale, and I do not intend to re-cover much of that ground in this post. The Southern Foodways Alliance has dedicated significant resources to documenting the history and practice of tamale making in the Mississippi Delta. Check out their extensive oral history project, at https://www.southernfoodways.org/oral-history/hot-tamale-trail/ For good measure, here’s an equally interesting story in “Roads and Kingdoms” magazine about the futile quest for that perfect hot tamale in the rural Delta region of Issaquena County, The Hot Tamales of Issaquena County, and how such legends abound in the land William Faulkner described as a doomed wilderness “which the little puny humans swarmed and hacked at in a fury of abhorrence and fear like pygmies about the ankles of a drowsing elephant.”

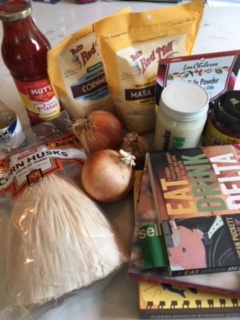

After consulting several excellent sources, including “The Southern Foodways Alliance Community Cookbook,” “Eat Drink Delta,” by journalist Susan Puckett of the Atlanta Journal–Constitution and “Screen Doors and Sweet Tea,” by Delta native and Paris-trained chef Martha Hall Foose, the recipe I followed looked pretty similar to the one found here, reduced by half, https://www.seriouseats.com/recipes/2011/04/cook-the-book-mississippi-delta-hot-tamales-recipe.html

First, let’s talk briefly about the process, and what I learned for future efforts. Making the tamales took me about five hours total. If and when I do it again, I would spread this across two days, making the pork filling the first day and then focusing on the dough, assembly and simmering the next day. I was almost too exhausted at the end of the process to enjoy the hot tamales. Fortunately, the leftovers continued to be very tasty.

When it comes to rolling the tamales, I would make smaller, more tightly rolled tamales and then bundle them in twine, as I have seen others do on videos, to secure them for the simmering process. Finally, I would endeavor to practice a bit more patience in the simmering of the tamales. I started removing them from the simmer bath right at the one hour mark, but a number of them needed some additional cooking. The microwave helped fix these errors, but I will more carefully test the doneness of the tamales before removing them from the simmer next time.

Now, to the more interesting questionof why Delta hot tamales. Much has also been written about the mysterious allure of the Mississippi Delta, the region scholar James Cobb described as the Most Southern Place on Earth. Like the backstory of tamales, I am not going to summarize that voluminous body of literature. My connection to the Delta is more personal. I’m a kid from the Mississippi Gulf Coast, a cultural universe apart from the Delta. But my dad was raised in the Delta town of Greenwood, and he loved to tell stories of his seemingly mythological childhood there. His glamorous Delta family members made a living growing and selling cotton, that is when they weren’t fighting wars, winning golf tournaments or tossing back highballs in the lobby of the Peabody. The family still owns farmland in the Delta, but few of my cousins are farmers. In fact, many of them have moved on to far-flung places including New York, Chicago, San Francisco and even Hong Kong.

I’ve got plenty of Delta stories and tall tales to unpack, most of them passed down to me from my father, who had a deeply ambivalent view of his iconic home region. For present purposes, I will share one of my own fonder memories of visiting the Delta, a story that includes eating hot tamales, twice.

In the mid-2000s, my eight-year-old son Emmet and I traveled to Memphis and the Delta to visit my dad and attend the annual blues festival in Helena, Arkansas. My dad, nomadic by nature, was living at the time in Hernando, Miss., just south of Memphis. We played golf at Overton Park in Memphis, where my grandfather caddied as a young lad before going on to a career as a professional golfer. We toured Sun Records of Elvis fame and ate ribs and tamales on Beale Street. After spending part of a very hot day at the blues festival in Helena, home of the famous King Biscuit Flour Hour radio show, we repaired to the nearby Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Miss., and then ate some more tamales at Morgan Freeman’s Ground Zero Blues Club. I do not have distinct memories of those tamales, other than knowing that they were a special regional treat. I have stronger taste memories of eating another plate of tamales about a year later, also with dad, at Doe’s Eat Place in Greenville, another distinctly Delta venue regularly celebrated by Julia.

The trip with Emmet was a success in almost every way in that we were able to enjoy two of the Delta’s main attractions, the blues and its distinct foodways, and to pass several pleasant days with my often-volatile father, who was on his best behavior for his eager and enthusiastic grandson. The whole experience, at least in my own pantheon of personal memories, was ideal, a perfect Delta tale like something out of one Julia’s columns!

In addition to tackling tamales, I also honored Julia Reed this past week by listening to the entire audible version of her lovely 2018 book of essays “South Toward Home,” read aloud in her distinctive, Scotch-laced southern drawl. I also made a modest donation – something I plan to do each time I post here going forward — of $25 dollars to the Emeril Lagasse Foundation (ELG), and I would encourage you to do the same on both scores. Future donations will go to ELG, the Lee Initiative or the Oregon Food Bank. Thank you very much for spending a little time with me.

bread. I dreaded going to school on Monday morning. My stomach would churn as anxiety washed over me; the prospect of another week of school would seem more than I could possibly handle. I have spent my whole life struggling with some form of this fear, which might come as a shock to many people who have known me casually or even worked with me, although it will be no surprise to anybody who knows me well. The one bright spot on those grammar school Mondays, and many Mondays and other days thereafter, were those earthy, salty, slightly spicy red beans and rice. They provided solace as I struggled to manage my nerves and get through the day.

bread. I dreaded going to school on Monday morning. My stomach would churn as anxiety washed over me; the prospect of another week of school would seem more than I could possibly handle. I have spent my whole life struggling with some form of this fear, which might come as a shock to many people who have known me casually or even worked with me, although it will be no surprise to anybody who knows me well. The one bright spot on those grammar school Mondays, and many Mondays and other days thereafter, were those earthy, salty, slightly spicy red beans and rice. They provided solace as I struggled to manage my nerves and get through the day.