“One can only face in others what one can face in oneself.”

James Baldwin, “Nobody Knows My Name”

My paternal grandmother was uninterested in food. She mostly lived on meal-replacement drinks, coffee and cigarettes. She was well-educated and well-read, an exemplary member of the Greatest Generation. Her husband and brothers served in both theaters of World War II, and her oldest brother gave his life when his plane was shot down over Mussolini’s Italy. Despite her extensive travels and years living in urbane Miami, she was Southern to her core both in her embrace of the region’s rich literary, cultural and political history and in her unfortunate views on race.

One of the few foods regularly found in my grandmother’s refrigerator was a container of store-bought pimento cheese, a culinary nod to her Southern roots. My grandmother was also fond of the golf champion Bobby Jones, a true superstar of the pre-War era, and the golf tournament he founded in his native Georgia, the Masters. Her golf pro husband, my grandfather Buck White, competed in the Masters twice during his tournament-playing career, and they returned on several other occasions as spectators. Pimento cheese sandwiches are a signature concession item at the Masters, revered to the point that a change in sandwich vendors sparked a minor controversy a few years ago.

The 2020 Masters, which concluded this past Sunday, was played off season because of the coronavirus pandemic. The tournament traditionally takes place in April. The 2020 Masters also marked a moment of transition for the tournament host, the exclusive Augusta National Country Club in Augusta, Georgia. In the lead-up to the tournament, the club announced that it will honor Lee Elder, the first black player to compete in the Masters, as an honorary starter at next year’s tournament along with Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player. The club also announced financial support for Paine College, a historically black college located in Augusta, Georgia.

As I have done for many years now, I made pimento cheese for my Master’s viewing pleasure. Fortunately, I recently found the perfect pimento cheese recipe from the cookbook “Soul,” by celebrated Atlanta-based chef Todd Richards, who champions black food culture and fellow chefs, particularly during this most challenging period for restaurants. To learn more about Richards’ journey from his native Memphis to Atlanta and from obscurity to fame, check out this Southern Fork podcast interview. I have tried many different pimento cheese recipes, and Richards’ version is by far the best.

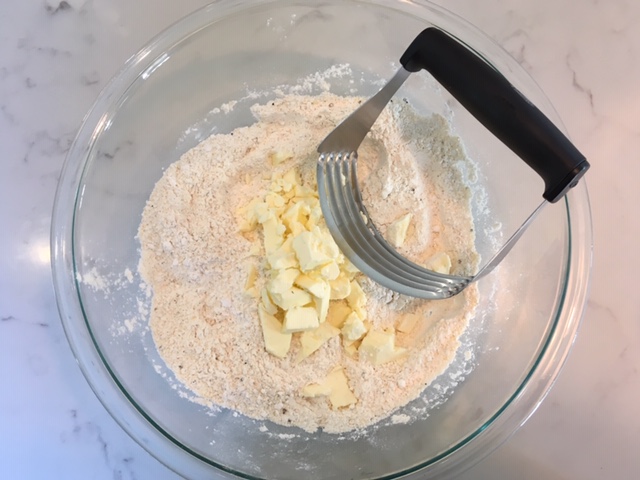

I paired the pimento cheese with another recipe from that same book, Atlanta biscuit maven Erika Council’s Black Pepper-Thyme Cornmeal Biscuits, along with Rose City Pepperheads pepper jelly, French salted butter, local honey and smoked ham from the Portland salumi purveyor Olympia Provisions. Council is another Southern food luminary, whose tantalizing Instagram feed at bombbiscuitatl is well worth adding to your feed. Listen to this illuminating interview with her on the excellent Southbound podcast with Tommy Tomlinson.

The combination of Richards’s pimento cheese and Council’s cornmeal biscuits were a perfect representation of the modern, soulful South, a place where the tropes of the Old South get reimagined through a vision of the diverse voices representing the region’s present and future.

Georgia has certainly been on my mind in more ways than one of late with the Peach State breaking blue, going for President-Elect Biden earlier this month, plus the two upcoming Senate runoffs that will potentially change the balance of power in our national government. Given my overall despondency with the current politics of the South, I am heartened by what’s happening in Georgia, particularly in the Atlanta area. This progress is a byproduct of the hard work of many people, including high-profile voting rights activist Stacy Abrams, who has focused like a laser on restoring integrity to the election system both in Georgia and around the nation. Abrams spent her early years living in the same town where I grew up, Gulfport, Mississippi, but given the de facto segregation of the era, it is unlikely our paths would have ever crossed.

The events of this year, including the nationwide response to the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, have raised my consciousness about the corrosive role racism continues to play in undermining our country’s ability to live into its promise and potential. I’ve been hitting the books, reading or re-reading writers like James Baldwin, Ibram X. Kendi, Bryan Stevenson and others. I’ve also been reflecting on the way being white and privileged have played into my opportunities and blinded me to the full impact of racism. I have been long focused on issues of race, civil rights and Southern history. I wrote an undergraduate thesis on the Mississippi novelist William Faulkner’s deconstruction of the myth of the Old South, influenced, in part, by my grandmother’s much earlier scholarship on Faulkner during her years at Vassar. My thesis applied postmodern literary analysis to illuminate racial ironies embedded both in Faulkner’s narratives and the historical myths he was challenging.

Faulkner’s literary achievement was monumental, and his vision of race and race relations was imbued with insight. But his writing, obsessed with aesthetic and historical analysis, ultimately lacked the moral force required to push for real change. By the end of his career, fellow writers like Baldwin were holding him accountable for these failings. In pushing back against Faulkner’s call for more time to let justice prevail, Baldwin in “Nobody Knows My Name” concludes: “There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.” I fear that I may have fallen into a similar, if more pedestrian, passive state, interested in important matters, but waiting for the right time to act and, until then, content to stand on the sidelines watching and analyzing.

I loved my grandmother, who passed away in 2000, and remain deeply grateful for the gifts she provided to me, including financial assistance with my formal education and encouraging my interest in history, politics and literature. At the same time, I anguish over her views on race, which were consistent with her time and background yet nonetheless an affront to decency. I also regret my own silence about those views. Had I shared my disagreement, maybe she would have been willing to reconsider her outlook on such matters. That would have been a victory, however small, indeed.

Is the Masters’ reconsideration of its own racial past a victory worth celebrating or simply the triumph of symbol over substance? I can’t really say, but as my sense of social consciousness growns, even at this advanced age, my enthusiasm for the Masters and other symbols of elitism wanes.

I still love certain aspects of my native South, its food, literature, music and hospitality. But I abhor much of the South’s embrace of Trumpism and the backlash against the election of President Obama and marriage equality and LGBTQ rights. To that end, my interest in Southern food and culture continues to point me toward an appreciation of the role that black writers, artists, musicians and chefs have played in shaping this culture, while holding in equipoise the truth of enduring racism and the cultural, economic, spiritual and political damage that racism has done to the beloved community.

An Episcopal priest friend once told me that God’s will for us can be found at the intersection of our talents and the world’s needs. My talents are scant and don’t extend far beyond the interests and skills on display right here. The world’s needs, particularly when it comes to justice and love, are immense. How do I bring my abiding interests together into an action plan that will allow me to step out of what Baldwin describes at the “lukewarm bath” of my own illusions about myself and my community so as to claim some small victory for justice and make some modest but meaningful difference in this world?

These are good questions, and immensely important to me. Until my action plan comes into sharper focus, I suppose I will just keep scribbling my notes here about food and fear and future challenges, using what Faulkner described in his soaring Nobel Speech as man’s puny inexhaustible voice still talking long after the last ding dong of doom has clanged and faded.

This week I made two separate $25 donations, one to City Harvest NYC and the other to Stacy Abrams’s Fair Fight. Thank you for spending a little time with me.